What is today’s date? If you answered this question with March 14, 2026 (read March the fourteenth, two thousand and twenty-six), you should go on reading.

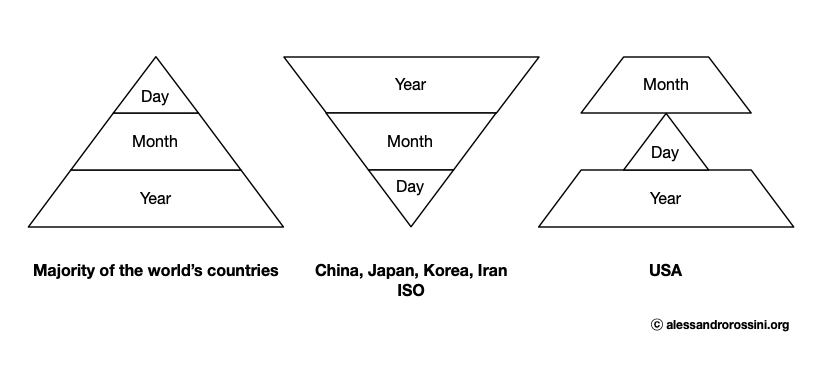

The day-month-year date format (e.g., 14 March 2026) is officially adopted by the vast majority of the world’s countries.

The year-month-day date format (e.g., 2026-03-14) is officially adopted by China, Japan, Korea, and Iran, and is also the date format of the ISO 8601 standard.

The month-day-year date format (e.g., March 14, 2026) is officially adopted by the USA only (although contamination of this format can be found in a few other countries). Like most standards adopted in the USA, the month-day-year date format is bizarre at best, as shown in the following illustration:

Yet, nowadays…

The month-day-year format is used by a large number of people speaking English as a foreign language, who adopt Americanisms like these without thinking them through. Unfortunately, this is the case even in Europe, despite the fact that every European country–including the UK–officially adopts the day-month-year format.

Long story short: if you live outside the USA but use the month-day-year format when writing or speaking in English, you are doing it wrong. You do not suddenly use miles, pounds, and Fahrenheit when writing or speaking in English, right? Then please, in the interest of logic, do not use the month-day-year date format either. 🙂 Keep using the day-month-year or year-month-day date formats, like you learned in school.

For everyday conversations, use the day-month-year date format. The variants d MMMM yyyy or d MMM yyyy (e.g., 14 March 2026 or 14 Mar 2026) increase readability and avoid misunderstandings.

For filename prefixes, use the year-month-day date formats. The variant yyyy-mm-dd (e.g., 2026-03-14) ensures that alphabetical sorting corresponds to date sorting.

So, once again, what is today’s date? It is 14 March 2026 (read the fourteenth of March two thousand and twenty-six).